Washington, DC – At the national scale, the U.S. is likely to face a shortage of over 5,300 critical care physicians due to COVID-19, or about one for every hospital in the United States, according to an updated model from Array Advisors. The model projects the net demand for critical care physicians in each state as a result of COVID-19, accounting for both the projected demand for ICU beds and the potential reduction in providers due to infection of the healthcare workforce.

As COVID-19 cases continue to surge across the country and hospitals fill up, health system operator’s original concern of the supply of beds and ventilators has shifted to the real limiting factor: staffing.

While the rise in cases is driving the scramble to find adequate staffing, there is a critical difference between what we saw at the beginning of the pandemic and what we are seeing now. Cases are rising across the country, making it even more difficult for staff to be deployed from areas with lower case counts to those with greater needs. Even in cases where that is possible, it will come with a high cost to systems already struggling financially as they halt elective cases and bear the burden of purchasing PPE.

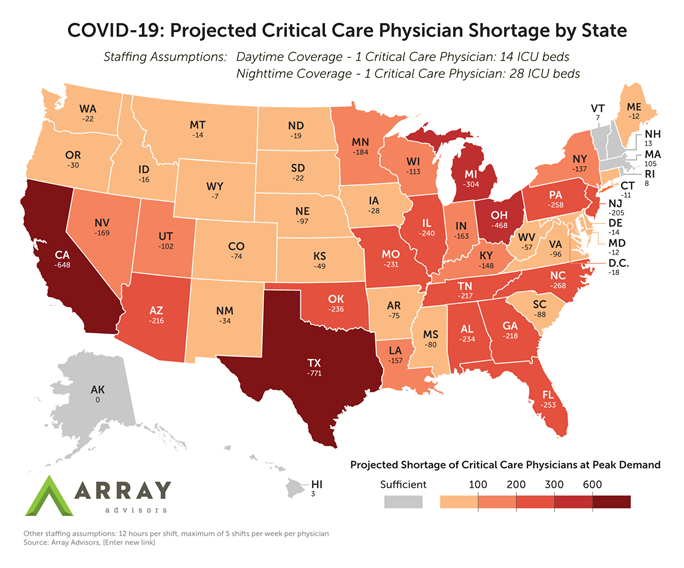

Shortages Projected in Most States

Array’s model calculates physician shortages at the projected peak in demand for critical care in each state (according to IHME projections), assuming that the recommended ratio of one intensivist for every 14 ICU beds1 is maintained during the day, and a stretch ratio of one intensivist for every 28 is used at night. Forty-four states and the District of Columbia are expected to experience deficits at peak demand, ranging from 7 (Wyoming) to 771 (Texas) additional critical care physicians needed. Six states – Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont, Hawaii, and Alaska – are projected to have sufficient critical care physicians at peak.

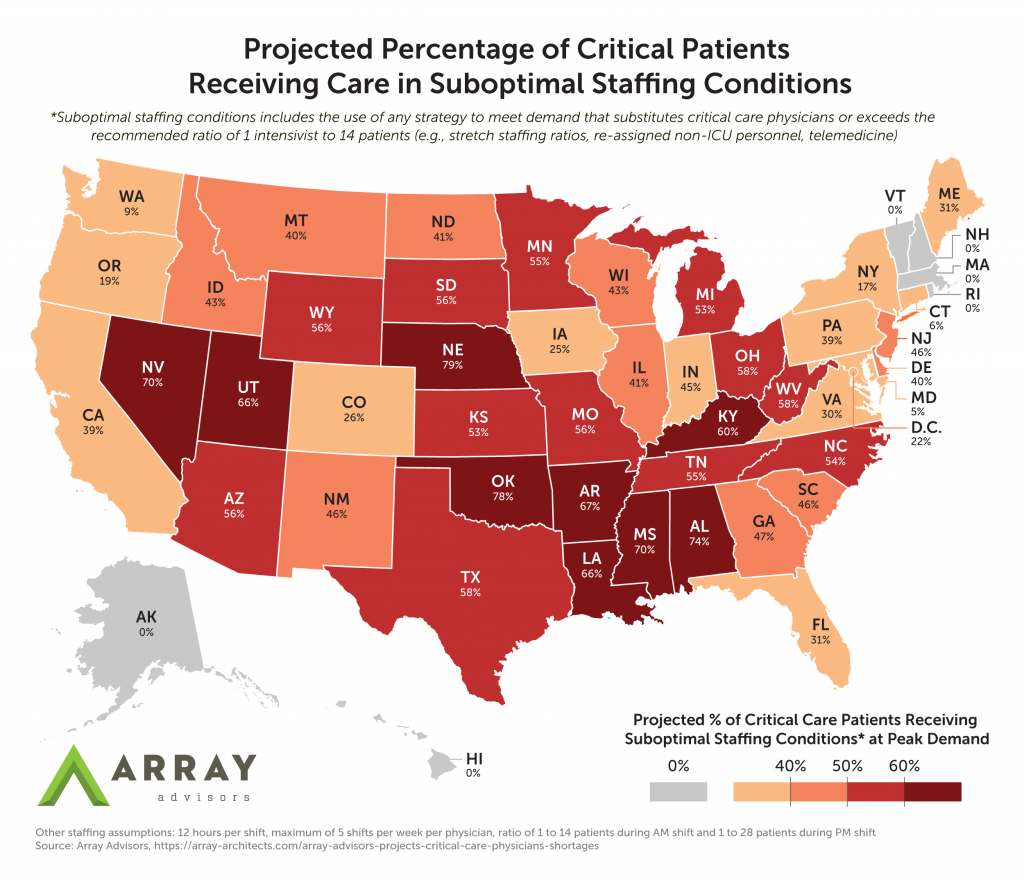

How will this shortage of critical care physicians impact patients? If hospitals are unable to increase their number of intensivists, they will still need to meet the demand for care and will have no choice but to do so through alternative means. Whether they stretch their staffing ratios, utilize non-ICU clinicians, or use telemedicine to increase coverage, the reality is that they will have to provide care that differs from the standard. In the map below, we have projected the percentage of critical care patients who are likely to receive such alternative care as a result of the critical care physician shortage. Based on these projections, over 30 states will have to provide alternative care to 40% or more of critical care patients.

Stretching Staffing Ratios Comes with the Risk of Worse Outcomes

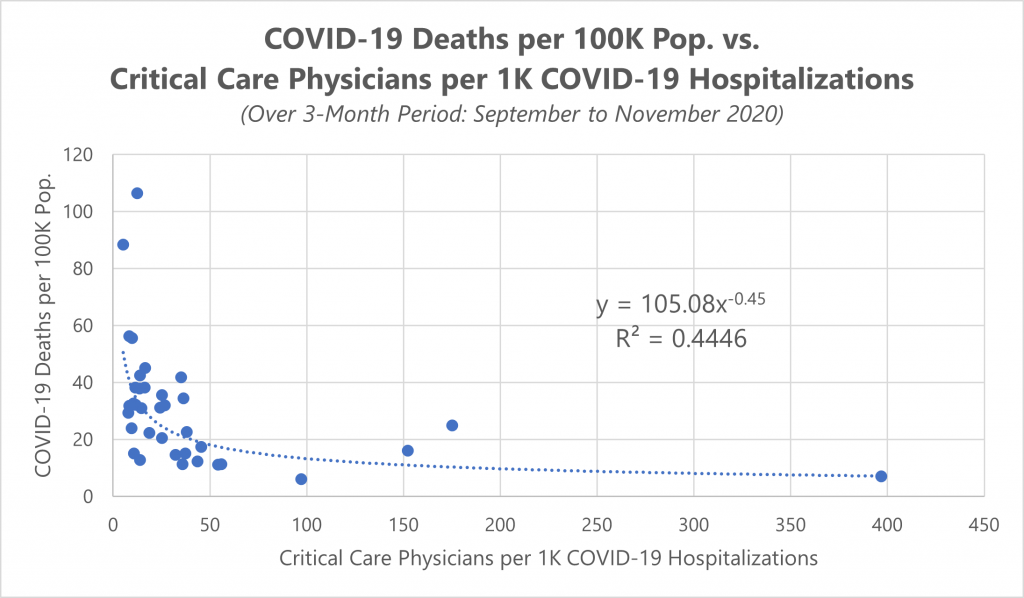

With limited options for increasing staff numbers, operators may have to resort to flexing staffing ratios beyond the recommended standard. However, with the stretching of the staffing model comes the risk of worse outcomes, such as higher mortality rates. Based on data for the months of September through November (a period in which new standards of care were followed nationally), we have observed a moderate correlation between the supply of intensivists per COVID-19 hospitalization and the overall COVID-19 mortality rate in each state.

*This model excludes 15 states that do not report cumulative hospitalizations.

As one would expect, a higher supply of intensivists is associated with a lower mortality rate. This relationship accounts for almost half of the variation in mortality rate across states.

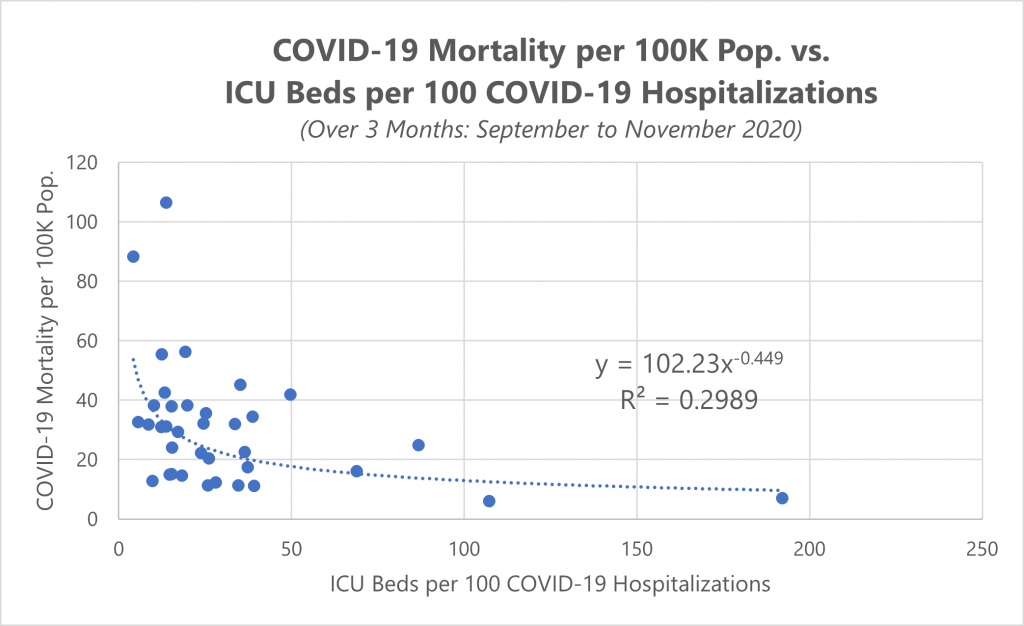

We observed a similar, but weaker relationship between the supply of ICU beds per hospitalization (as a proxy for advanced care capabilities) and mortality rate, which further emphasizes the relatively higher importance of adequate physician staffing in determining COVID-19 outcomes.

*This model excludes 15 states that do not report cumulative hospitalizations.

Systems Will Need to Think Outside the Box to Close Gaps

Hospitals facing a potential shortage of critical care physicians will have limited options for ensuring coverage of ICU beds. Given the results of the model, sharing of critical care physicians between states will be an extremely challenging exercise in timing, if not altogether impossible. It may still be feasible to strategically deploy reserve medics to the areas with the highest need and transfer them as demand wanes, for as long as the “curves” across the country do not approach their peaks at the same time. According to the IHME projections, the peak dates range from early December to late February.

Even if the United States is fortunate enough to avoid a confluence of demand curves, hospitals will still have to find other ways to close the gaps. Now that we are well into the pandemic, many hospitals are already employing strategies such as utilizing other specialists with critical care experience (e.g., pulmonologists, emergency physicians, hospitalists)2, stretching staffing ratios, and utilizing AI to assist with triaging and decision-making, which gives physicians more time for patient care.3

What else can hospitals do? The options we have identified below may have seemed impossible earlier in the pandemic, and some will undoubtedly come with significant risks, but health systems and governing bodies may have no choice but to take them:

- Asymptomatic physicians: Allow asymptomatic physicians who test positive for COVID-19 to return to work and provide care via tele-ICU or directly to patients if appropriate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) is available.

- International support: Establish coverage (particularly at night) through international clinicians via telemedicine. Given the number of ICU beds per capita as a proxy for expertise4, it is possible that Japan and South Korea may have specialists to share via telemedicine. Germany may also be a good candidate, pending its ability to get the pandemic under control. As many doctors will speak English, language should not be a major barrier. This solution would be particularly useful where community hospitals do not have deep critical care benches and the normal hubs are burnt out. However, such a program would have to be ramped up very quickly and would require the waiving of U.S. licensing rules.

- Bubble team: Create a “bubble team” to support critical care workers. Following the NBA’s example, systems could establish a “clean team” in a bubble whose job it is to make the care team’s lives easier and keep them safe and focused (e.g., drive them to and from the hospital, clean their house, buy food, provide childcare).

- Statewide command: Establish teams at the state level (working with state authorities) to redistribute patients as needed. If some parts of a state are a hot spot, they would move patients or clinicians. Individual systems with burnt out providers will not have an incentive to fully function as one state team, so experts in clinical operations may need to step in.

—

The healthcare industry needs innovative solutions to battle the unprecedented coronavirus pandemic. Array Advisors, Array Analytics, and Array Architects will continue to provide ideas, design, and data-informed tools to help support their clients on the front lines of caring for our nation. For more tools from Array, visit our COVID-19 Resource Hub.

Study FAQ

How did you define “Critical Care Physicians” in your model?

The physician counts in our Pivotal tool are sourced from the National Plan & Provider Enumeration System (NPPES). We selected providers with Medicare Provider Type “Physician/Internal Medicine” and a “Critical Care Medicine” specialization (taxonomy code: 207RC0200X).

Does your model account for the demand in ICU care not related to COVID-19?

Yes. We assumed the baseline demand for ICU coverage would remain the same and that COVID-19 patients would create new demand.

While most COVID-19 patients will require care outside of the ICU, we assumed that care will be provided by other physicians. In other words, our model does not assume that Critical Care Physicians will be needed to cover any other type of bed/setting for COVID-19 patients or any other patients.

Are there other specialists that can provide coverage in the ICU in lieu of a Critical Care Physician?

Some health systems do have other specialists with critical care expertise (such as pulmonologists) in addition to their fellowship-trained critical care intensivists. These specialists may be able to rotate and help cover ICU beds as peak demand hits different hospitals within a service area. This option is most likely feasible at Academic Medical Centers, but most community hospitals will not have that bench to draw from.

Can systems look to Advanced Practice Providers (APPs) to cover the shortage gap?

Critical care advanced practice practitioners are routinely used to care for critically ill patients, typically under the supervision of an intensivist. Baseline staffing models vary by state and even by hospital. During this crisis, we are hopeful that stretching of these models will be possible to meet demand. The Society of Critical Care Medicine has published one potential “crisis model” for tiered staffing that would depend heavily on the use of teams led by a critical care APP and a non-ICU physicians to enable each Critical Care Physician to oversee the care of a much larger group of patients.

In some states, such as Florida, scope of practice bills have been signed into law that allow nurse practitioners to work more independently. This will enable physicians who are now needed in the ICU or anywhere else in the hospital to be backfilled by these advanced practitioners, who in turn can over care for patients without COVID-19 or perhaps even low-acuity COVID-19 patients.

Citations

1. Ward NS, et al.; Members of Society of Critical Care Medicine Taskforce on ICU Staffing. Intensivist/patient ratios in closed ICUs: a statement from the Society of Critical Care Medicine Taskforce on ICU Staffing. Crit Care Med. 2013 Feb;41(2):638-45.

2. Sweigart JR, Aymond D, Burger A, et al.: Characterizing Hospitalist Practice and Perceptions of Critical Care Delivery. J Hosp Med 2018; 13:6–12

3. Libassi, M. “AI can help COVID-19 clinical decision making, Feinstein Institutes research shows,” Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research at Northwell Health. July 2020.

4. Conrad, K. “Countries with Most Critical Care Beds per Capita,” WorldAtlas, August 2020.

About Array

Recognized as a leader in healthcare facility design, consulting and technology, Array offers knowledge-based, data-informed services, including planning, architecture, interior design, transformation and asset advisory services. Using Lean as a foundation for a unique process-led approach, Array’s deliverables use data and technology to leverage real-time patient and real estate market trends required by today’s healthcare organizations. The company’s devotion to a healthcare-exclusive practice springs from the belief in the power of design and technology to improve patient outcomes, maximize operational efficiencies, and increase staff satisfaction.

Media Contact

Craig Meaney

Communications Manager

610-755-6488

@ArrayArch

cmeaney@array-architects.com